Ada’s legacy

Ada Lovelace had a brilliant mind, and in her correspondence with eminent scientists such as Charles Babbage and Michael Faraday, she shared ideas so ahead of their time that they are still relevant today. In particular, she was very creative and could make connections between seemingly unrelated topics to generate very original ideas. This is remarkable considering that in the early 1800’s science and mathematics were exclusively the domain of men, and male Victorian attitudes towards the capabilities of women, especially in the sciences, were extremely limiting.

Here, we’ll explore her work with Babbage as well as some of the more farsighted ideas, and how she has influenced thinking about computing and artificial intelligence which is still relevant today.

The design of Babbage’s mechanical computer (the Analytical Engine) was very intricate and to make its components accurately enough, most of the work had to be done by hand, by skilled artisans. This made the design very expensive, and in 1840 Babbage travelled to Italy as part of a fund-raising mission. He gave a lecture about the workings of the Analytical Engine at the University of Turin, complete with charts, drawings, models, and mechanical notations. In the audience was Luigi Menabrea, a mathematician who subsequently published a scientific paper about Babbage’s lecture. This was the first ever published account of the Engine’s design, but as it was written in French, a friend of Babbage’s suggested that Ada Lovelace should translate it into English. Babbage also encouraged her to augment the account with a set of appendices.

She did so in 1843, and at the end of her translation she wrote a series of seven ‘notes’ (A through G). Her notes went into much greater depth about the workings and potential uses of the Analytical Engine. They were three times as long as Menabrea’s paper, laying out a more ambitious plan for the Engine than even Babbage had envisaged.

In these notes, she put forward a number of theories which were so far ahead of their time that they only began to be addressed more than a century later, and are still relevant to Artificial Intelligence today.

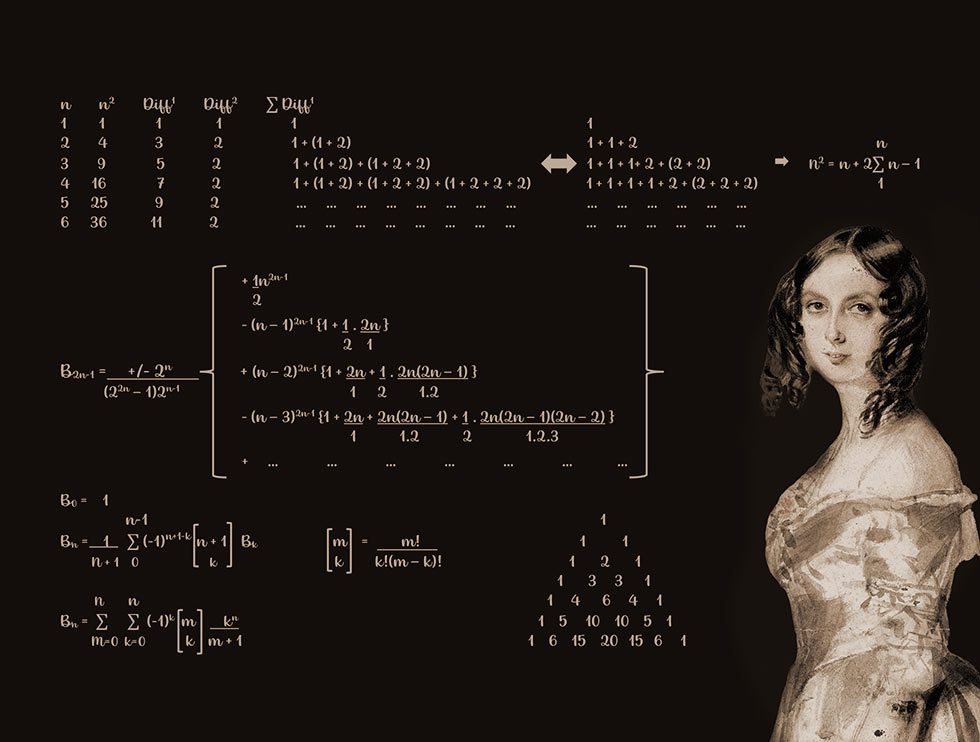

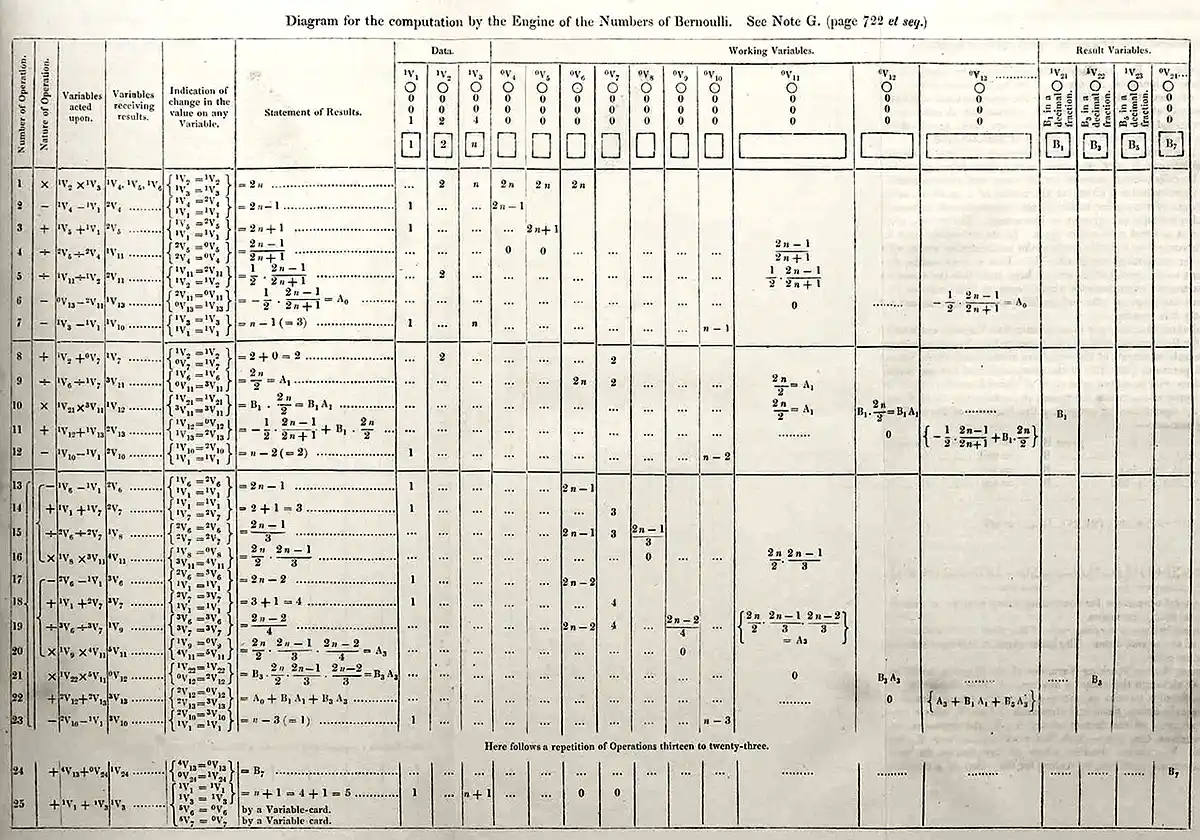

‘Note G’ is perhaps the most famous, and is considered to be the world’s first computer program. It is a complex algorithm arranged in blocks, to organise the different steps of the calculations described. The blocks are also repeated (‘looped’), to repeat similar calculations. Looping is a mainstay of modern computer programming and means a programmer can shorten what could be hundreds of lines of code to just a few. This allows the code to be written once and repeated as many times as needed, cutting out mistakes and making it more likely the program will run as expected.

Ada’s algorithm has even been reproduced in modern computer programming languages. In 1979 the US department of defence developed a computer language which was named ‘Ada’ in her honour, and is still in use today in specialised applications such as space exploration.

In ‘Note A’, Ada also considered other applications for the Analytical Engine beyond engineering calculations, such as composing music. This seems natural to us today, but was highly original two hundred years ago.

“Again, it [the analytical engine] might act upon other things besides number….supposing that the fundamental relations of pitched sounds in the science of harmony and of musical composition were susceptible to such expression and adaptations, the [analytical] engine might compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music to any degree of complexity and extent”.

While Ada foresaw the potential of computers in this way, her ‘Note G’ also speaks of their possible limitations:

“The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything.

It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform.

It can follow analysis; but it has no power of anticipating any analytical relations or truths….

Only when computers originate things should they be believed to have minds”.

The great computer scientist Alan Turing was aware of Ada’s work, and made reference to it in a famous paper he wrote in 1950. He argued that it should be possible to ‘order’ a computing machine to be original, by programming it to produce answers that we cannot predict. Turing believed computers could be original, and referred to Ada’s views as ‘Lady Lovelace’s Objection’, which he argued against in his paper.

The debate still rages today on whether Artificial Intelligence can be truly original, or can only reuse in different ways what it has already been ‘taught’. In fact, in 2001 a test for artificial intelligence was developed and named the ‘Lovelace Test’ in her honour, revisiting her original thinking:

“Can a machine originate a valuable novelty which it hasn’t been specifically programmed to do, where the process is repeatable and reproducible, and can the programmer explain how the programme managed it?”

We can definitely say that Ada Lovelace was a thoroughly modern scientist, and perhaps she may even have the last word on Artificial Intelligence!